← Back

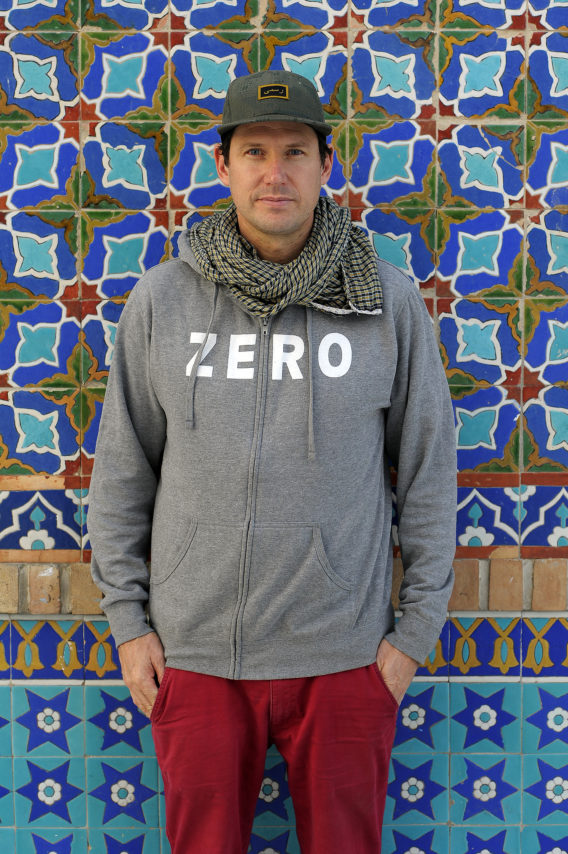

Oliver Percovich, Founder - Skateistan

Interview, 23 April 2019

“You never change things by fighting the existing reality. To change something, build a new model that makes the existing model obsolete.”

/R Buckminster Fuller

Oliver Percovich grew up in Australia and Papua New Guinea and first came to Kabul, Afghanistan in 2007, looking for work as a research scientist. A country ravaged by war for the better part of the last 40 years, and also one of the most gender-segregated places on the planet.

As an avid skateboarder, Percovich had brought a few of his boards with him, which quickly drew the attention from the local youth who started joining him in the streets of Kabul. Especially the girls and young women seemed to take their new-found activity to heart.

The crowd got larger by each day and the Australian started organizing skateboarding sessions in the Afghan capital, quickly realizing there was a loophole in Afghan society for the notoriously anti-authoritarian sport. No one in Kabul had ever seen a skateboard before – and could therefore not deem the activity culturally inappropriate.

Over the ensuing months, skateboarding grew to become a positive outlet for local children, affording them a sense of community and meaning, and Oliver Percovich decided to dedicate himself full-time towards establishing a non-profit organization which was already known internally as: Skateistan, which means place or land of skateboarding.

Skateistan was initially launched using grassroots tactics and funding. Today, 12 years on, it has become an award winning NGO that has attracted significant donations from the art community, private donors and foreign governments, built several skateparks, launched an education program which has seen hundreds of children go back to school, provide a platform for Afghan girls and young women to take part in society and has expanded its operations to Cambodia and South Africa.

But above all, Oliver Percovich and his initiative has managed to provide a whole generation of Afghan youths with a sense of purpose and joy. In a country where 64 percent of the population is below the age of 25 and are in desperate need of hope for a meaningful future.

We caught up with the founder of Skateistan from their headquarters in Berlin to discuss the impact Skateistan is having, the therapeutic effects of skateboarding and why education is key for youth to prosper in places where hope is hard to come by.

What is your own background like?

– It’s quite varied. I’ve been a skateboarder since the age of five, so I have a long history there. I studied chemistry and worked as a researcher at a university as well as being an entrepreneur within the food industry in Australia. I also worked with the indigenous people in health services, so I’m definitely a jack of all trades, master of none. I came into Afghanistan and Skateistan without any background in international development at all. No special expertise whatsoever, and I think that actually worked to my advantage. I set up Skateistan by looking at what was needed instead of following a set formula.

What was the fundraising process for Skateistan like in the early stages?

– From the

“For a child who is in fight-or-flight mode the whole time, skateboarding can be a very regulative activity and a very important one.”

I can imagine setting something like this up in Afghanistan comes with quite a few challenges. What were some of the biggest obstacles you had to face?

– It all had very much to do with having the right people being a part of the project from the start. The location is, for obvious reasons, not for everybody. Some people who got involved were able to adapt to living and working in Kabul, but not everyone. That meant we had a relatively high staff and volunteer turnover in the early days. We had to work out ways to attract and keep volunteers at first, and then to create paid positions so we could keep the right people. Getting stuff done requires good people. There was also a huge cross-cultural challenge of how to get foreigners and Afghans coming together, working towards a common goal. Another challenge, but also an advantage, was not having any money, or not having very much money. It meant we had to think creatively about a lot of the things we were doing. Not having money also meant not having to worry about attracting the wrong people. Large projects with lots of funding behind them often attracts the wrong people, especially in Afghanistan.

How were you able to introduce skateboarding to the local community and the elders without it being seen as a “western” phenomenon?

– I realized very early that in order to succeed in attracting people to our project we couldn’t have skateboarding seen as a western activity. I didn’t show them any tricks or anything, I just put the skateboard down at their feet and said “hey, interact with this thing”. I did my best to exclude anything like skateboarding fashion, music, videos or magazines from the equation. It was important to me that the families of the students didn’t see it as a cultural invasion of any kind. Getting the parents involved early on was also very important for the children to stay on and take part in our activities. I quickly understood that I needed to have Afghan instructors and staff to be able to interact with other Afghans, in order to keep the interaction as fluid as possible.

Skateboarding has a long history of helping to overcome social divisions, were you at all surprised that it had that same effect even in this case?

– I was very aware of the role skateboarding could play in terms of breaking down barriers between people from different backgrounds. In my own

In a war-torn country like Afghanistan and a city so plagued by violence and socio-economic turmoil like Johannesburg – what do you think your efforts are worth in terms

– I think it comes down to what sort of opportunities exist for youth to try things out or to have an outlet. When you live in a warzone or a place that has high levels of poverty, the stress in your everyday life can be truly immense. A lot of the children in Johannesburg, for example, face violence from their parents on a daily basis and also see it within their communities. Same in Afghanistan, poverty creates large amounts of stress in their lives. An activity like skateboarding can

“We’ve seen our students getting into jobs, becoming journalists, setting up their own NGOs and getting involved in activities that are not very common for young people coming from those kinds of backgrounds.”

What are some of the more immediate results you have seen from incorporating the educational programs into the activities of Skateistan?

– We’ve seen students getting into jobs, becoming journalists, setting up their own NGOs and getting involved in activities that are not very common for young people coming from those kinds of backgrounds. Over 500 of our kids have gotten back into regular school in Afghanistan so far, thanks to our Back-to-School programs and accelerated learning platforms. It is

What do you envision being the next step for Skateistan?

– We look to continue going into difficult regions. We are setting up in central Afghanistan, in Bamian. We are also aiming to establish ourselves in the Middle East, we are currently working on setting up a skate school in Jordan. We have also launched the Goodpush Alliance, which is a platform for spreading our knowledge. Over the past 10 years a lot of other skate-projects have popped up all around the world and we are very excited to share what we have

For more – and to donate – please visit:

www.skateistan.org